Submitted by Michael Gyory:

“Days are scrolls – write on them what you want to be remembered.” – Bachya ibn Pakuda, 11th century rabbi

I realize that like my parents I have shut the door on my past. I have never returned to my childhood home. Never. This, even though I have spent the majority of my adult life living less than a half an hour away.

I spent my first seventeen years in the modest brick ranch house at the end of a dirt road in Katonah, New York. It was the only place I had ever lived. I shared a small bedroom with my brother, he in the top bunk and me on the bottom of our trundle bed. My parents sold the house (part of the divorce fallout) during my first semester in college. While home for the Christmas break, I slept on the living room floor of the empty house the night before the closing, under the excuse of protecting the empty house from vandalism. Ridiculous. The house was too remote and isolated to ever be vandalized. Growing up, I never even had a key to the place, and on the rare occasion that I came home and found it locked, I learned to climb in through a window. Still I could not part with my only home.

I have never again driven the kilometer down the narrow lane from Cherry Street where we walked daily to await the school bus. Never returned to the steep gravel driveway where we sledded those many winters. I have heard that the dirt road is now paved, that the empty spaces on the lane are now filled in with houses. Enough change to take away its rural charm. I have never shown my wife, my son, my girlfriend or anyone.

Look forward, never back.

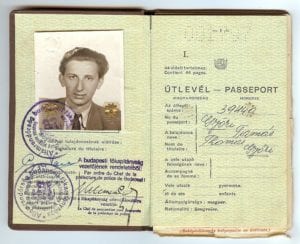

On the last day of my vacation in Budapest in 2017, I decided to go again to see my father’s childhood home. My grandfather, who I would never meet, had constructed the home for his family. Like him, my father would become a builder and build his own home in America. I knew the address and I had been there once before. My father had shown it to us (myself and my brother and sister) when we were visiting Hungary in 1983. The house and the neighborhood had changed little since he had left over three decades before. Still, he rang the bell at 8 Mikszath Utca (street) on a tree lined residential street in the Pesterszerber. It was a solid one-story house with dark brown shutters on beige stucco walls. There was a detached garage and small yard tucked behind a four foot concrete privacy wall. He chatted with the woman who met him at the gate and he told her that he had grown up there and was showing the house to his American children. We were not invited in. We did not see much else of the town, we did not drive through the business district or find the street where my mother grew up or see his school or favorite soccer field.

I thought that I could get a better feel for where my parents grew up if I took the subway to the closest stop and walked through the neighborhood to locate his childhood home. Together with my son Jacob, and armed with the GPS on my smart phone, we walked several miles through pleasant suburbs to reach Pesterszerber. It was a hot and humid August afternoon as we passed through the flat and unremarkable landscape. The closer to our destination, the more rundown the neighborhood. On his street every house is fenced off from the street and often dogs barked and strained at us as we marched down the sidewalk. We found that his house is being gutted and renovated. There are only gapping holes where windows once stood and a large addition is being added. I am struck by the coincidence that at the same time in America, I am gutting and renovating a commercial warehouse in New York. It is the final building that my father constructed which our family still owns.

Although it was a Friday, there was no one working and yet again I cannot enter the yard. So we take some pictures and resume our trek. We return to the subway station via commercial streets which proved to simply be dirtier, hotter and unshaded. Jacob, sweaty and tired, makes me check my GPS several times to confirm that we are not headed in the wrong direction. Although we make it back to the subway, perhaps I have been misdirected. I feel no closer to my parents for having trod their streets seventy years after their emigration. I find that the edifice of my father’s former life stands merely as a reminder to a lost people.

I recommit myself to looking forward.